HISTORY

Bali was inhabited by about 2000 BC by

Austronesian peoples who migrated originally from

Taiwan through

Maritime Southeast Asia.

[3] Culturally and linguistically, the Balinese are thus closely related to the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago, the Philippines, and Oceania.

[4] Stone tools dating from this time have been found near the village of Cekik in the island's west.

[5]

Balinese culture was strongly influenced by Indian and Chinese, and particularly

Hindu culture, beginning around the 1st century AD. The name

Bali dwipa ("Bali island") has been discovered from various inscriptions, including the Blanjong pillar inscription written by

Sri Kesari Warmadewa in 914 AD and mentioning "Walidwipa". It was during this time that the complex irrigation system

subak was developed to grow rice. Some religious and cultural traditions still in existence today can be traced back to this period. The Hindu

Majapahit Empire (1293–1520 AD) on eastern

Java founded a Balinese

colony in 1343. When the empire declined, there was an exodus of intellectuals, artists, priests, and musicians from Java to Bali in the 15th century.

The first

European contact with Bali is thought to have been made in 1585 when a

Portuguese ship foundered off the

Bukit Peninsula and left a few Portuguese in the service of

Dewa Agung.

[6] In 1597 the

Dutch explorer

Cornelis de Houtman arrived at Bali and, with the establishment of the

Dutch East India Company in 1602, the stage was set for colonial control two and a half centuries later when Dutch control expanded across the Indonesian archipelago throughout the second half of the nineteenth century (see

Dutch East Indies). Dutch political and economic control over Bali began in the 1840s on the island's north coast, when the Dutch pitted various distrustful Balinese realms against each other.

[7] In the late 1890s, struggles between Balinese kingdoms in the island's south were exploited by the Dutch to increase their control.

The Dutch mounted large naval and ground assaults at the Sanur region in 1906 and were met by the thousands of members of the royal family and their followers who fought against the superior Dutch force in a suicidal

puputan defensive assault rather than face the humiliation of surrender.

[7] Despite Dutch demands for surrender, an estimated 1,000 Balinese marched to their death against the invaders.

[8] In the

Dutch intervention in Bali (1908), a similar massacre occurred in the face of a Dutch assault in

Klungkung. Afterwards the Dutch governors were able to exercise administrative control over the island, but local control over religion and culture generally remained intact. Dutch rule over Bali came later and was never as well established as in other parts of Indonesia such as Java and

Maluku.

In the 1930s, anthropologists

Margaret Mead and

Gregory Bateson, and artists

Miguel Covarrubias and

Walter Spies, and musicologist

Colin McPhee created a western image of Bali as "an enchanted land of aesthetes at peace with themselves and nature", and western tourism first developed on the island.

[9]

Balinese dancers show for tourists,

Ubud.

Imperial Japan occupied Bali during

World War II, during which time a Balinese military officer,

Gusti Ngurah Rai, formed a Balinese 'freedom army'. The lack of institutional changes from the time of Dutch rule however, and the harshness of war requisitions made Japanese rule little better than the Dutch one.

[10] Following Japan's Pacific surrender in August 1945, the Dutch promptly returned to Indonesia, including Bali, immediately to reinstate their pre-war colonial administration. This was resisted by the Balinese rebels now using Japanese weapons. On 20 November 1946, the

Battle of Marga was fought in Tabanan in central Bali. Colonel I Gusti Ngurah Rai, by then 29 years old, finally rallied his forces in east Bali at Marga Rana, where they made a

suicide attack on the heavily armed Dutch. The Balinese battalion was entirely wiped out, breaking the last thread of Balinese military resistance. In 1946 the Dutch constituted Bali as one of the 13 administrative districts of the newly proclaimed

State of East Indonesia, a rival state to the Republic of Indonesia which was proclaimed and headed by

Sukarno and

Hatta. Bali was included in the "Republic of the United States of Indonesia" when the Netherlands recognised Indonesian independence on 29 December 1949.

The 1963 eruption of

Mount Agung killed thousands, created economic havoc and forced many displaced Balinese to be

transmigrated to other parts of Indonesia. Mirroring the widening of social divisions across Indonesia in the 1950s and early 1960s, Bali saw conflict between supporters of the traditional

caste system, and those rejecting these traditional values. Politically, this was represented by opposing supporters of the

Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and the

Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI), with tensions and ill-feeling further increased by the PKI's land reform programs.

[7] An attempted coup in Jakarta was put down by forces led by General Suharto. The army became the dominant power as it instigated

a violent anti-communist purge, in which the army blamed the PKI for the coup. Most estimates suggest that at least 500,000 people were killed across Indonesia, with an estimated 80,000 killed in Bali, equivalent to 5% of the island's population.

[11] With no Islamic forces involved as in Java and Sumatra, upper-caste PNI landlords led the extermination of PKI members.

[12]

As a result of the 1965/66 upheavals, Suharto was able to manoeuvre Sukarno

out of the presidency, and his

"New Order" government reestablished relations with western countries. The pre-War Bali as "paradise" was revived in a modern form, and the resulting large growth in tourism has led to a dramatic increase in Balinese standards of living and significant foreign exchange earned for the country.

[7] A bombing in 2002 by militant

Islamists in the tourist area of

Kuta killed 202 people, mostly foreigners. This attack, and

another in 2005, severely affected tourism, bringing much economic hardship to the island. Tourist numbers have now returned to levels before the bombings.

Geography

The island of Bali lies 3.2 km (2 mi) east of

Java, and is approximately

8 degrees south of the

equator. Bali and Java are separated by

Bali Strait. East to west, the island is approximately 153 km (95 mi) wide and spans approximately 112 km (69 mi) north to south; its land area is 5,632 km².

Bali's central mountains include several peaks over 3,000 metres. The highest is

Mount Agung (3,142 m), known as the "mother mountain" which is an active

volcano. Mountains range from centre to the eastern side, with Mount Agung the easternmost peak. Bali's volcanic nature has contributed to its exceptional fertility and its tall mountain ranges provide the high rainfall that supports the highly productive agriculture sector. South of the mountains is a broad steadily descending area where most of Bali's large rice crop is grown. The northern side of the mountains slopes more steeply to the sea and is the main coffee producing area of the island, along with rice, vegetables and cattle. The longest river,

Ayung River, flows approximately 75 km.

The island is surrounded by

coral reefs.

Beaches in the south tend to have white sand while those in the north and west have

black sand. Bali has no major waterways, although the Ho River is navigable by small

sampan boats. Black sand beaches between Pasut and Klatingdukuh are being developed for tourism, but apart from the seaside temple of

Tanah Lot, they are not yet used for significant tourism.

The largest city is the provincial capital,

Denpasar, near the southern coast. Its population is around 491,500(2002). Bali's second-largest city is the old colonial capital,

Singaraja, which is located on the north coast and is home to around 100,000 people. Other important cities include the beach resort,

Kuta, which is practically part of Denpasar's urban area; and

Ubud, which is north of Denpasar, and is known as the island's cultural centre.

Three small islands lie to the immediate south east and all are administratively part of the

Klungkung regency of Bali:

Nusa Penida,

Nusa Lembongan and

Nusa Ceningan. These islands are separated from Bali by the Badung Strait.

To the east, the

Lombok Strait separates Bali from

Lombok and marks the

biogeographical division between the fauna of the

Indomalayan ecozone and the distinctly different fauna of

Australasia. The transition is known as the

Wallace Line, named after

Alfred Russel Wallace, who first proposed a transition zone between these two major

biomes. When sea levels dropped during the

Pleistocene ice age, Bali was connected to

Java and

Sumatra and to the mainland of Asia and shared the Asian fauna, but the deep water of the Lombok Strait continued to keep Lombok and the

Lesser Sunda archipelago isolated.

Ecology

The

Bali Starling is found only on Bali and is critically endangered.

Bali lies just to the west of the

Wallace Line, and thus has a fauna which is Asian in character, with very little Australasian influence, and has more in common with Java than with Lombok. An exception is the

Yellow-crested Cockatoo, a member of a primarily Australasian family. There are around 280 species of birds, including the critically endangered

Bali Starling, which is

endemic. Others Include

Barn Swallow,

Black-naped Oriole,

Black Racket-tailed Treepie,

Crested Serpent-eagle,

Crested Treeswift,

Dollarbird,

Java Sparrow,

Lesser Adjutant,

Long-tailed Shrike,

Milky Stork,

Pacific Swallow,

Red-rumped Swallow,

Sacred Kingfisher,

Sea Eagle,

Woodswallow,

Savanna Nightjar,

Stork-billed Kingfisher,

Yellow-vented Bulbul,

White Heron,

Great Egret.

Until the early 20th century, Bali was home to several large mammals: the wild

Banteng,

Leopard and an endemic

subspecies of Tiger, the

Bali Tiger. The Banteng still occurs in its domestic form, while leopards are found only in neighboring Java, and the Bali Tiger is extinct. The last definite record of a Tiger on Bali dates from 1937, when one was shot, though the subspecies may have survived until the 1940s or 1950s.

[13] The relatively small size of the island, conflict with humans, poaching and habitat reduction drove the Tiger to extinction. This was the smallest and rarest of all Tiger subspecies and was never caught on film or displayed in zoos, while few skins or bones remain in museums around the world. Today, the largest mammals are the

Javan Rusa deer and the

Wild Boar. A second, smaller species of deer, the

Indian Muntjac, also occurs.

Squirrels are quite commonly encountered, less often the

Asian Palm Civet, which is also kept in coffee farms to produce

Kopi Luwak.

Bats are well represented, perhaps the most famous place to encounter them remaining the Goa Lawah (Temple of the Bats) where they are worshipped by the locals and also constitute a tourist attraction. They also occur in other cave temples, for instance at Gangga Beach. Two species of

monkey occur. The

Crab-eating Macaque, known locally as “kera”, is quite common around human settlements and temples, where it becomes accustomed to being fed by humans, particularly in any of the three “monkey forest” temples, such as the popular one in the

Ubud area. They are also quite often kept as pets by locals. The second monkey, far rarer and more elusive is the

Silver Leaf Monkey known locally as “lutung”. They occur in few places apart from the

Bali Barat National Park. Other, rarer mammals include the

Leopard Cat,

Sunda Pangolin and

Black Giant Squirrel.

Snakes include the

King Cobra and

Reticulated Python. The

Water Monitor can grow to an impressive size and move surprisingly quickly.

The rich coral reefs around the coast, particularly around popular diving spots such as

Tulamben,

Amed, Menjangan or neighboring

Nusa Penida, host a wide range of marine life, for instance

Hawksbill Turtle,

Giant Sunfish,

Giant Manta Ray,

Giant Moray Eel,

Bumphead Parrotfish,

Hammerhead Shark,

Reef Shark,

barracuda, and

sea snakes.

Dolphins are commonly encountered on the north coast near

Singaraja and

Lovina.

Many plants have been introduced by humans within the last centuries, particularly since the 20th century, making it sometimes hard to distinguish what plants are really native. Among the larger trees the most common are:

Banyan trees,

Jackfruit,

coconuts,

bamboo species,

acacia trees and also endless rows of

coconuts and

banana species. Numerous flowers can be seen:

hibiscus,

frangipani,

bougainvillea,

poinsettia,

oleander,

jasmine,

water lily,

lotus,

roses,

begonias, orchids and

hydrangeas exist. On higher grounds that receive more moisture, for instance around

Kintamani, certain species of

fern trees,

mushrooms and even

pine trees thrive well. Rice comes in many varieties. Other plants with agricultural value include:

salak,

mangosteen,

corn, Kintamani

orange,

coffee and

water spinach.

Administrative divisions

The province is divided into 8

regencies (

kabupaten) and 1

city (

kota). Unless otherwise stated, the regency's capital:

Economy

Three decades ago, the Balinese economy was largely agriculture-based in terms of both output and employment. Tourism is now the largest single industry; and as a result, Bali is one of Indonesia’s wealthiest regions. About 80% of Bali's economy depends on tourism.

[14] The economy, however, suffered significantly as a result of the terrorist bombings

2002 and

2005. The tourism industry is slowly recovering once again.

Agriculture

Although tourism produces the GDP’s largest output, agriculture is still the island’s biggest employer;

[15][citation needed] most notably

rice cultivation. Crops grown in smaller amounts include fruit, vegetables,

Coffea arabica and other

cash and subsistence crops.

[citation needed] Fishing also provides a significant number of jobs. Bali is also famous for its

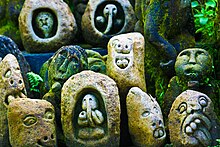

artisans who produce a vast array of handicrafts, including

batik and

ikat cloth and clothing,

wooden carvings, stone carvings, painted art and silverware. Notably, individual villages typically adopt a single product, such as wind chimes or wooden furniture.

The Arabica coffee production region is the highland region of Kintamani near

Mount Batur. Generally, Balinese coffee is processed using the wet method. This results in a sweet, soft coffee with good consistency. Typical flavors include lemon and other citrus notes.

[16] Many coffee farmers in Kintamani are members of a traditional farming system called Subak Abian, which is based on the

Hindu philosophy of "Tri Hita Karana”. According to this philosophy, the three causes of happiness are good relations with God, other people and the environment. The Subak Abian system is ideally suited to the production of fair trade and organic coffee production. Arabica coffee from Kintamani is the first product in Indonesia to request a

Geographical Indication.

[17

Tourism

The tourism industry is primarily focused in the south, while significant in the other parts of the island as well. The main tourist locations are the town of

Kuta (with its beach), and its outer suburbs of Legian and

Seminyak (which were once independant townships), the east coast town of

Sanur (once the only tourist hub), in the center of the island

Ubud, to the south of the

Ngurah Rai International Airport,

Jimbaran, and the newer development of

Nusa Dua and

Pecatu.

The American government lifted its travel warnings in 2008. As of 2009, the Australian government still rates it at a 4 danger level (the same as several countries in

central Africa) on a scale of 5.

An offshoot of tourism is the growing real estate industry. Bali real estate has been rapidly developing in the main tourist areas of Kuta, Legian, Seminyak and Oberoi. Most recently, high-end 5 star projects are under development on the Bukit peninsula, on the south side of the island. Million dollar villas are being developed along the cliff sides of south Bali, commanding panoramic ocean views. Foreign and domestic (many Jakarta individuals and companies are fairly active) investment into other areas of the island also continues to grow. Land prices, despite the worldwide economic crisis, have remained stable.

In the last half of 2008, Indonesia's currency had dropped approximately 30% against the US dollar, providing many overseas visitors value for their currencies. Visitor arrivals for 2009 were forecast to drop 8% (which would be higher than 2007 levels), due to the worldwide economic crisis which has also affected the global tourist industry, but not due to any travel warnings.

Bali's tourism economy survived the terrorist bombings of 2002 and 2005, and the tourism industry has in fact slowly recovered and surpassed its pre-terrorist bombing levels; the longterm trend has been a steady increase of visitor arrivals. The Indonesian Tourism Ministry expected a record number of visitor arrivals in 2010.

[18]

Bali received the Best Island award from

Travel and Leisure in 2010. The award was presented in the show "World's Best Awards 2010" in New York, on 21 July. Hotel Four Seasons Resort Bali at

Jimbaran also received an award in the category of "World Best Hotel Spas in Asia 2010". The award was based on a survey of travel magazine

Travel + Leisure readers between 15 December 2009 through 31 March 2010, and was judged on several criteria. The Ayana Resort received the designation; #1 Spa in the world by Conde Naste's Traveller Magazine for 2010 by their readers poll . The island of Bali won because of its attractive surroundings (both mountain and coastal areas), diverse tourist attractions, excellent international and local restaurants, and the friendliness of the local people.

Transportation

The

Ngurah Rai International Airport is located near Jimbaran, on the

isthmus at the southernmost part of the island.

Lt.Col. Wisnu Airfield is found in north-west Bali.

A coastal road surrounds the island, and three major two-lane arteries cross the central mountains at passes reaching to 1,750m in height (at Penelokan). The Ngurah Rai Bypass is a four-lane expressway that partly encircles Denpasar and enables cars to travel quickly in the heavily populated south. Bali has no railway lines.

December 2010: Government of Indonesia has invited investors to build Tanah Ampo Cruise Terminal at

Karangasem, Bali amounted $30 million.

[19]

Demographics

The population of Bali is 3,151,000 (as of 2005). There are an estimated 30,000 expatriates living in Bali.

[20]

Religion

Unlike most of

Muslim-majority Indonesia, about 93.18% of Bali's population adheres to

Balinese Hinduism, formed as a combination of existing

local beliefs and

Hindu influences from mainland

Southeast Asia and

South Asia. Minority religions include

Islam (4.79%),

Christianity (1.38%), and

Buddhism (0.64%). These figures do not include immigrants from other parts of Indonesia.

When Islam surpassed Hinduism in

Java (16th century), Bali became a refuge for many Hindus. Balinese Hinduism is an amalgam in which gods and demigods are worshipped together with Buddhist heroes, the spirits of ancestors, indigenous agricultural deities and sacred places. Religion as it is practiced in Bali is a composite belief system that embraces not only theology, philosophy, and mythology, but ancestor worship, animism and magic. It pervades nearly every aspect of traditional life.

Caste is observed, though less strictly than in India. With an estimated 20,000

puras (temples) and shrines, Bali is known as the "Island of a Thousand Puras", or "Island of the Gods".

[21]

Balinese Hinduism has roots in Indian Hinduism and in Buddhism, and adopted the animistic traditions of the indigenous people. This influence strengthened the belief that the gods and goddesses are present in all things. Every element of nature, therefore, possesses its own power, which reflects the power of the gods. A rock, tree, dagger, or woven cloth is a potential home for spirits whose energy can be directed for good or evil. Balinese Hinduism is deeply interwoven with art and ritual. Ritualizing states of self-control are a notable feature of religious expression among the people, who for this reason have become famous for their graceful and decorous behavior.

[22]

Apart from the majority of Balinese Hindus, there also exist

Chinese immigrants whose traditions have melded with that of the locals. As a result, these Sino-Balinese not only embrace their original religion, which is a mixture of Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism, but also find a way to harmonize it with the local traditions. Hence, it is not uncommon to find local Sino-Balinese during the local temple's

odalan. Moreover, Balinese Hindu priests are invited to perform rites alongside a Chinese priest in the event of the death of a Sino-Balinese.

[23] Nevertheless, the Sino-Balinese claim to embrace Buddhism for administrative purposes, such as their Identity Cards.

[24]

Language

Balinese and

Indonesian are the most widely spoken languages in Bali, and the vast majority of Balinese people are

bilingual or

trilingual. There are several indigenous Balinese languages, but most Balinese can also use the most widely spoken option: modern common Balinese. The usage of different Balinese languages was traditionally determined by the

Balinese caste system and by clan membership, but this tradition is diminishing.

English is a common third language (and the primary foreign language) of many Balinese, owing to the requirements of the

tourism industry.

Culture

The famous dancer i Mario, picture taken 1940.

Bali is renowned for its diverse and sophisticated art forms, such as painting, sculpture, woodcarving, handcrafts, and performing arts. Balinese percussion orchestra music, known as

gamelan, is highly developed and varied. Balinese performing arts often portray stories from Hindu epics such as the

Ramayana but with heavy Balinese influence. Famous Balinese dances include

pendet,

legong,

baris,

topeng,

barong,

gong keybar, and

kecak (the monkey dance). Bali boasts one of the most diverse and innovative performing arts cultures in the world, with paid performances at thousands of temple festivals, private ceremonies, or public shows.

[25]

The Hindu New Year,

Nyepi, is celebrated in the spring by a day of silence. On this day everyone stays at home and tourists are encouraged to remain in their hotels. But the day before that large, colourful sculptures of

ogoh-ogoh monsters are paraded and finally burned in the evening to drive away evil spirits. Other festivals throughout the year are specified by the Balinese

pawukon calendrical system.

Balinese dancers wearing elaborate headgear, photographed in 1929. Digitally restored.

Celebrations are held for many occasions such as a tooth-filing (coming-of-age ritual), cremation or

odalan (temple festival). One of the most important concepts that Balinese ceremonies have in common is that of

désa kala patra, which refers to how ritual performances must be appropriate in both the specific and general social context.

[26] Many of the ceremonial art forms such as

wayang kulit and

topeng are highly improvisatory, providing flexibility for the performer to adapt the performance to the current situation.

[27] Many celebrations call for a loud, boisterous atmosphere with lots of activity and the resulting aesthetic,

ramé, is distinctively Balinese. Oftentimes two or more

gamelan ensembles will be performing well within earshot, and sometimes compete with each other in order to be heard. Likewise, the audience members talk amongst themselves, get up and walk around, or even cheer on the performance, which adds to the many layers of activity and the liveliness typical of

ramé.

[28]

Kaja and

kelod are the Balinese equivalents of North and South, which refer to ones orientation between the island’s largest mountain Gunung Agung (

kaja), and the sea (

kelod). In addition to spatial orientation,

kaja and

kelod have the connotation of good and evil; gods and ancestors are believed to live on the mountain whereas demons live in the sea. Buildings such as temples and residential homes are spatially oriented by having the most sacred spaces closest to the mountain and the unclean places nearest to the sea.

[29]

Most temples have an inner courtyard and an outer courtyard which are arranged with the inner courtyard furthest

kaja. These spaces serve as performance venues since most Balinese rituals are accompanied by any combination of music, dance and drama. The performances that take place in the inner courtyard are classified as

wali, the most sacred rituals which are offerings exclusively for the gods, while the outer courtyard is where

bebali ceremonies are held, which are intended for gods and people. Lastly, performances meant solely for the entertainment of humans take place outside the walls of the temple and are called

bali-balihan. This three-tiered system of classification was standardized in 1971 by a committee of Balinese officials and artists in order to better protect the sanctity of the oldest and most sacred Balinese rituals from being performed for a paying audience.

[30]

Tourism, Bali’s chief industry, has provided the island with a foreign audience that is eager to pay for entertainment, thus creating new performance opportunities and more demand for performers. The impact of

tourism is controversial since before it became integrated into the economy, the Balinese performing arts did not exist as a capitalist venture, and were not performed for entertainment outside of their respective ritual context. Since the 1930s sacred rituals such as the

barong dance have been performed both in their original contexts, as well as exclusively for paying tourists. This has led to new versions of many of these performances which have developed according to the preferences of foreign audiences; some villages have a

barong mask specifically for non-ritual performances as well as an older mask which is only used for sacred performances.

[31]

Balinese society continues to revolve around each family's ancestral village, to which the cycle of life and religion is closely tied.

[32] Coercive aspects of traditional society, such as

customary law sanctions imposed by traditional authorities such as village councils (including "

kasepekang", or

shunning) have risen in importance as a consequence of the democratization and decentralization of Indonesia since 1998.

[32]

[edit] See also

- ^ Indonesia's Population: Ethnicity and Religion in a Changing Political Landscape. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 2004.

- ^ http://www.citypopulation.de/Indonesia-MU.html

- ^ Taylor (2003), pp. 5, 7; Hinzler (1995)

- ^ Hinzler (1995)

- ^ Taylor (2003), p. 12; Lonely Planet (1999), p. 15.

- ^ Willard A. Hanna (2004). Bali Chronicles. Periplus, Singapore. ISBN 0-7946-0272-X p.32

- ^ a b c d Vickers (1995)

- ^ Haer, p.38

- ^ Friend, Theodore "Indonesian destinies" Harvard University Press, 2003 ISBN 0-674-01137-6, 9780674011373 Length 628 pages P111

- ^ Haer, p.39-40

- ^ Friend (2003), p. 111; Ricklefs (1991), p. 289; Vickers (1995)

- ^ Ricklefs, p. 289.

- ^ IUCN, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species accessed 24 June 2010

- ^ Desperately Seeking Survival. Time. 25 November 2002.

- ^ On history of rice-growing related to museology and the rice terraces as part of Bali's cultural heritage see: Marc-Antonio Barblan, "D'Orient en Occident: histoire de la riziculture et muséologie" in ''ICOFOM Study Series, Vol.35 (2006), pp.114–131. LRZ-Muenchen.de and "Dans la lumière des terrasses: paysage culturel balinais, Subek Museumet patrimoine mondial (1er volet) "in Le Banian (Paris), juin 2009, pp.80–101, Pasarmalam.free.fr

- ^ "Diverse coffees of Indonesia". Specialty Coffee Association of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080802030333/http://www.sca-indo.org/diverse-coffees-indonesia/. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- ^ "Book of Requirements for Kopi Kintamani Bali", page 12, July 2007

- ^ Indonesian Tourism Ministry Expects More Visitors in 2010

- ^ http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/business/infrastructure-projects-in-indonesia-thrown-open-for-bids/412805

- ^ Ballots in paradise. Guardian.co.uk. 30 October 2008.

- ^ Everyday spirits. Theage.com.au. 3 May 2008.

- ^ Slattum, J. (2003) Balinese Masks: Spirits of an Ancient Drama. Indonesia, Asia Pacific, Japan, North America, Latin America and Europe Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd

- ^ Blogspot.com

- ^ Blogspot.com

- ^ Emigh, John (1996). Masked Performance: The Play of Self and Other in Ritual and Theatre. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 081221336X. The author is a Western theatre professor who has become a performer in Balinese topeng theater himself.

- ^ Herbst 1997, p. 1-2.

- ^ Foley and Sedana 2005, p. 208.

- ^ Gold 2005, p. 8.

- ^ Herbst 1997, p. 1-2.; Gold 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Gold 2005, p. 18-26.

- ^ Sanger 1988, p. 90-93.

- ^ a b Belford, Aubrey (12 October 2010). "Customary Law Revival Neglects Some Balinese". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/13/world/asia/13iht-bali.html. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

[edit] References

- Miguel Covarrubias, Island of Bali, 1946. ISBN 962-593-060-4

- Foley, Kathy; Sedana, I Nyoman; Sedana, I Nyoman (Autumn 2005). "Mask Dance from the Perspective of a Master Artist: I Ketut Kodi on "Topeng"". Asian Theatre Journal (University of Hawai'i Press) 22 (2): 199–213.. doi:10.1353/atj.2005.0031.

- Friend, T. (2003). Indonesian Destinies. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01137-6.

- Gold, Lisa (2005). Music in Bali: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514149-0.

- Greenway, Paul; Lyon, James. Wheeler, Tony (1999). Bali and Lombok. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. ISBN 0-86442-606-2.

- Herbst, Edward (1997). Voices in Bali: Energes and Perceptions in Vocal Music and Dance Theater. Hanover: University Press of New England. ISBN 0-8195-6316-1.

- Hinzler, Heidi (1995) Artifacts and Early Foreign Influences. From Oey, Eric (Editor) (1995). Bali. Singapore: Periplus Editions. pp. 24–25. ISBN 962-593-028-0.

- Ricklefs, M. C. (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1300, Second Edition. MacMillan. ISBN 978-0333576892.

- Sanger, Annette (1988). "Blessing or Blight? The Effects of Touristic Dance-Drama on village Life in Singapadu, Bali". Come Mek Me Hol' Yu Han': the Impact of Tourism on Traditional Music (Berlin: Jamaica Memory Bank): 89–104..

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- Vickers, Adrian (1995), From Oey, Eric (Editor) (1995). Bali. Singapore: Periplus Editions. pp. 26–35. ISBN 962-593-028-0.

- Pringle, Robert (2004). Bali: Indonesia's Hindu Realm; A short history of. Short History of Asia Series. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-863-3.

[edit] Further reading

- Copeland, Jonathan (2010). Secrets of Bali: Fresh Light on the Morning of the World. Orchid Press. ISBN 978-974-524-118-3.

- McPhee, Colin (2003). A House in Bali. Tuttle Publishing; New edition, 2000 (first published in 1946 by J. Day Co). ISBN 978-9625936291.

- Shavit, David (2006). Bali and the Tourist Industry: A History, 1906–1942. McFarland & Co Inc. ISBN 978-0786415724.

- Vickers, Adrian (1994). Travelling to Bali: Four Hundred Years of Journeys. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-9676530813.

- Whitten, Anthony J.; Roehayat Soeriaatmadja, Suraya A. A. (1997). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. ISBN 978-9625930725.

- Wijaya, Made (2003). Architecture of Bali: A Source Book of Traditional and Modern Forms. Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0500341926.

Warung nasi sambel bejek matah hanya menawarkan daging ayam yang tentunya dapat dikonsumsi oleh semua kalangan.

Warung nasi sambel bejek matah hanya menawarkan daging ayam yang tentunya dapat dikonsumsi oleh semua kalangan. Warung nasi sambel bejek matah hanya menawarkan daging ayam yang tentunya dapat dikonsumsi oleh semua kalangan.

Warung nasi sambel bejek matah hanya menawarkan daging ayam yang tentunya dapat dikonsumsi oleh semua kalangan. Kalau ke Ubud, mampirlah ke Resto Bebek Bengil, resto yang berdiri sejak tahun 90an ini terletak di Jalan Hanoman Padang Tegal Ubud, kalau dalam bahasa Bali Bebek Bengil berarti Bebek dekil atau kotor yang penuh lumpur, tapi ini beda, justru bebek bengil ini dicari banyak orang karena hidangan bebek goreng yang sangat renyah, rasanya pun gurih dan nikmat!

Kalau ke Ubud, mampirlah ke Resto Bebek Bengil, resto yang berdiri sejak tahun 90an ini terletak di Jalan Hanoman Padang Tegal Ubud, kalau dalam bahasa Bali Bebek Bengil berarti Bebek dekil atau kotor yang penuh lumpur, tapi ini beda, justru bebek bengil ini dicari banyak orang karena hidangan bebek goreng yang sangat renyah, rasanya pun gurih dan nikmat! Seporisi bebek ternyata setengah bebek kecil , nasi putih, sambel bawang matah (sambel khas Bali) dan urab khas Bali atau lawar. Harganya pun mahal satu porsi bebek bengil berkisar 60 ribuan. Tapi harganya sesuai dong dengan suasana dan menu yang anda nikmati.

Seporisi bebek ternyata setengah bebek kecil , nasi putih, sambel bawang matah (sambel khas Bali) dan urab khas Bali atau lawar. Harganya pun mahal satu porsi bebek bengil berkisar 60 ribuan. Tapi harganya sesuai dong dengan suasana dan menu yang anda nikmati. Di penghujung tahun ini, jalan Gajah Mada dan kawasan Catur Muka (titik 0 km Denpasar) akan kembali menjadi pusat berlangsungnya sebuah perhelatan besar yaitu Denpasar Festival, dari tanggal 28 s/d 31 Desember 2009.

Di penghujung tahun ini, jalan Gajah Mada dan kawasan Catur Muka (titik 0 km Denpasar) akan kembali menjadi pusat berlangsungnya sebuah perhelatan besar yaitu Denpasar Festival, dari tanggal 28 s/d 31 Desember 2009.

Menu yang disajikan mulai dari :

Menu yang disajikan mulai dari :

Warung Mira Katrangan

Warung Mira Katrangan

Menu yang disajikan mulai dari :

Menu yang disajikan mulai dari :

Warung Mira Katrangan

Warung Mira Katrangan